The Square Atrium. The room served largely as a waiting room, the antechamber to various halls. The decoration dates from the 16th century, during the period of Doge Girolamo Priùli, who appears in Tintoretto’s ceiling painting with the symbols of his office, accompanied by allegories of Justice and Peace. The four corner scenes, probably by Tintoretto’s workshop, comprise biblical stories – perhaps an allusion to the virtues of the Doge – and allegories of the four seasons. The celebratory decor of the room was completed by four paintings of mythological scenes, which now hang in the antechamber to the Hall of the Full Council. Their place here has been taken by Girolamo Bassano’s The Angel appearing to the Shepherds and other biblical scenes that are, with reservations, attributed to Veronese.

The Four Doors Room. This room was the formal antechamber to the more important rooms in the palace, and the doors which give it its name are ornately framed in precious eastern marbles; each is surmounted by an allegorical sculptural group that refers to the virtues which should inspire those who took on the government responsibilities. The 1574 fire in this area damaged this room and those immediately after severely, but fortunately with no structural damage. The present decor is a work by Antonio da Ponte and design by Andrea Palladio and Antonio Rusconi. The coffered ceiling – with stucco decoration by Giovanni Cambi, known as Bombarda – contains frescoes of mythological subjects and of the cities and regions under Venetian dominion. Painted by Jacopo Tintoretto from 1578 onwards, this decorative scheme was designed to show a close link between Venice’s foundation, its independence, and the historical mission of the Venetian aristocracy – a program of self-celebration that could already be seen in the Golden Staircase. Amongst the paintings on the walls, one that stands out is Titian’s portrait of Doge Antonio Grimani (1521-1523) kneeling before Faith. On the easel stands a famous work by Tiepolo; painted between 1756 and 1758, it shows Venice receiving the gifts of the sea from Neptune.

Antechamber to the Hall of the Full Council. Formal antechamber where foreign ambassadors and delegations waited to be received by the Full Council, which was delegated by the Senate to deal with foreign affairs. This room was restored after the 1574 fire and so was its decor, with stucco-works and ceiling frescoes, similar to what one finds in the Hall of Four Doors. The central fresco by Veronese shows Venice distributing honors and rewards. The top of the walls is decorated with a fine frieze and other sumptuous fittings, including the fireplace between the windows and the fine doorway leading into the Hall of the Full Council, whose Corinthian columns bear a pediment surmounted by a marble sculpture showing the female figure of Venice resting on a lion and accompanied by allegories of Glory and Concord. Next to the doorways are four canvases that Jacopo Tintoretto painted for the Square Atrium, but which were brought here in 1716 to replace the original leather wall paneling. Each of the mythological scenes depicted is also an allegory of the Republic’s government. The Antechamber contains other famous works, including Paolo Veronese’s The Rape of Europe.

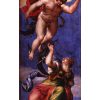

The Council Chamber. The Full Council which met in this room was comprised of two separate and independent organs of power, the Savi and the Signoria. The former was in its turn divided into the Savi del Consiglio, who concerned themselves mainly with foreign policy, the Savi di Terraferma, who were responsible for matters linked with Venice’s empire in mainland Italy; and the Savi agli Ordini, who dealt with maritime issues. The Signoria was made up of the three Heads of the Councils of Forty and members of the Minor Council, composed of the Doge and six councilors, one for each district into which the city of Venice is divided. The Full Council was mainly responsible for organizing and coordinating the work of the Senate, reading dispatches from ambassadors and city governors, receiving foreign delegations and promoting other political and legislative activity. Alongside these shared functions, each body had their own particular mandates, which made this body a sort of “guiding intelligence” behind the work of the Senate, especially in foreign affairs. The decor was designed by Andrea Palladio to replace that destroyed in the 1574 fire; the wood paneling of the walls and end tribune and the carved ceiling are the work of Francesco Bello and Andrea da Faenza. The splendid paintings set into that ceiling were commissioned from Veronese, who completed them between 1575 and 1578. This ceiling is one of the artist’s masterpieces and celebrates the Good Government of the Republic, together with the Faith on which it rests and the Virtues that guide and strengthen it. The first rectangular panel shows the St. Mark’s bell-tower behind the figures of Mars and Neptune, Lords of War and Sea respectively. The central panel shows the Triumph of Faith, and the rectangular panel closest to the tribune, Venice with Justice and Peace. Around there are some eight smaller, T-or L-shaped panels that depict the virtues of government. Veronese again produces the large canvas over the tribune in celebration of the Christian fleet’s victory over the Turks at the Battle of Lepanto on 7 October 1571 – a victory to which Venice made an essential contribution. The other paintings are by Tintoretto and show various Doges with the Christ, the Virgin and saints.

Senate Chamber. This hall was also known as the Sala dei Pregadi, because the Doge asked the members of the Senate to take part in the meetings held here. The Senate which met in this chamber was one of the oldest public institutions in Venice; it had first been founded in the 13th century and then gradually evolved over time, until by the 16th century it was the body mainly responsible for overseeing political and financial affairs in such areas as manufacturing industries, trade and foreign policy. In effect, it was a more limited sub-committee of the Great Council, and its members were generally drawn from the wealthiest Venetian families. The refurbishment after the 1574 fire took place during the 1580s, and once the new ceiling had been completed work started on the pictorial decoration, which seems to have been finished by 1595. In the works produced for this room by Tintoretto, Christ is clearly the predominant figure; perhaps this is a reference to the Senate ‘conclave’ which elected the Doge, who was then seen as being under the protection of the Son of God. The room also contains four paintings by Jacopo Palma il Giovane, which are linked with specific events of the Venetian history.

The Chamber of the Council of Ten. The Council of Ten that gives this room its name was set up after a conspiracy in 1310, when Bajamonte Tiepolo and other noblemen tried to overthrow the institutions of the State. Initially meant as a provisional body to try those conspirators, the Council of Ten is one of those many examples of Venetian institutions that were intended to be temporary but ended up becoming permanent. Its authority covered all sectors of public life and this power gave rise to the fame of the Council as a ruthless, all-seeing tribunal at the service of the ruling oligarchy, a court whose sentences were handed down rapidly after hearings held in secret. The assembly was made up of ten members chosen from the Senate and elected by the Great Council. These ten sat in council with the Doge and his six counselors, which accounts for the 17 semicircular outlines that one can still see in the chamber. The decoration of the ceiling was the work of Gian Battista Ponchino, with the assistance of a young Veronese and Gian Battista Zelotti. Carved and gilded, the ceiling is divided into 25 compartments decorated with images of divinities and allegories intended to illustrate the power of the Council of Ten that was responsible for punishing the guilty and freeing the innocent. It is very difficult to interpret each individual compartment because the artists often tend to overlap the traditional interpretation of a mythological event or figure with a reading that is specific to Venice and its history. Veronese’s paintings – from that of the old oriental figure to that showing Juno scattering her gifts on Venice – are particularly famous. The oval painting in the center, depicting Jove descending from the clouds to hurl thunderbolts at Vice, is however a copy of the original Veronese which Napoleon took to the Louvre.

The Compass Room. This is the first room on this floor dedicated to the administration of justice; its name comes from the large wooden compass surmounted by a statue of Justice, which stands in one corner and hides the entrance to the rooms of the three Heads of the Council of Ten and the State Inquisitors. This room, therefore, was the antechamber where those who had been summoned by these powerful magistrates waited to be called and the magnificent decor was intended to underline the solemnity of the Republic’s legal machinery, some of the most famous and efficient components of which were housed in these rooms. The decor dates from the 16th century, and once again it was Veronese who was commissioned to decorate the ceiling. Completed in 1554, the works he produced are all intended to exalt the “good government” of the Venetian Republic; the central panel, with St. Mark descending to crown the three Theological Virtues, is a copy of the original, now in the Louvre. Sansovino designed the large fireplace in 1553-54. Within the palace, all rooms that served in the exercise of justice were linked vertically. From the ground-floor prisons known as The Wells, to the Advocate’s Offices on the loggia floor, the Councils of Forty and the Hall of the Magistrates of Law on the first floor and the various courtrooms on this second floor, the progression culminated in the prisons directly under the roof, the famous Piombi or “Leads”. Stairways, corridors and vestibules interconnected all of these spaces. From this room, in fact, one can pass to the Armory and the New Prisons, on the other side of the Bridge of Sighs, or go straight down the Censors’ Staircase to pass into the rooms housing the councils of justice on the first floor.