VENETIA 1600

Births and rebirths

4 September 2021 – 5 June 2022

Venezia, Palazzo Ducale – Doge’s Apartments

![]()

I. INTRODUCTION

Venice stands apart. Perhaps no other city can boast such an astonishing physical setting or concentration of historic architecture.

For centuries Venice was one of Europe’s largest and richest cities, and easily the most sophisticated, an unequalled crossroads of people and ideas.

The unusual structure of its government ensured political stability for a millennium, earning it the title of La Serenissima, the Most Serene Republic, and sparking envy of the merchants of Venice across the globe.

Even today, Venice remains an ideal of urbanism: compact, walkable, a città a misura d’uomo (city on a human scale), sensitive to its environment, proud of its traditions, yet welcoming to outsiders.

Venice now celebrates 1600 years since its legendary founding in 421.

Yet it is not only Venice’s birth that is worthy of celebration, but its many rebirths as well. Venice has survived for so long, surmounting innumerable threats, because it has reinvented itself, time and again, in new and more adaptable guises.

Key events, monuments, and the many artistic and historical treasures in this exhibition provide a valuable roadmap for the city’s future.

Many of the challenges that confront Venice today were overcome through Venetian ingenuity decades or even centuries ago.

Understanding Venice’s past offers its inhabitants today – and those around the world who love this city – much of the knowledge that will be necessary for what the future requires.

II. THE CHOSEN CITY

As Venice became a wealthy and powerful city with an empire on both land and sea, Venetians began to recount stories of the city’s origins that prophesized a special destiny. According to tradition, Venice was founded at Rialto at the stroke of noon on the feast of the Annunciation, 25 March, in the year 421. Just as the Annunciation revealed that the Virgin Mary was chosen by God for the salvation of mankind, so Venice was the chosen city, inheritor of the Roman and Byzantine empires and protector of Christianity. The image of the Annunciation, one of the most common in Venetian art, alludes to this special status. So does the date of March 25, which Venetians chose whenever possible for laying the foundation stones of important buildings.

CITY OF SAINT MARK

In 828, Venetian merchants brought the body of the Evangelist Mark from Alexandria in Egypt, confirming Venice’s ascent to the first rank of cities. The saint’s relics were placed in a series of structures that eventually developed into the present basilica of San Marco. Mark became the Republic’s patron saint and the winged lion of Saint Mark its emblem, omnipresent in the city and its empire. The saint’s legend was absorbed into the history of the city. In one episode, an angel appeared to him as he passed through the lagoon, foretelling that one day his remains would come to rest there. In another, the saint himself miraculously appeared in the basilica of San Marco to reveal the location of his relics, which had been lost as the building was reconstructed. With the fall of Constantinople and the defeat of the Byzantines in 1204, Venice assumed the mantle of empire, bringing home building materials and countless precious objects from Constantinople and adopting the Byzantine style for its art and architecture. Some of the finest Byzantine objects from the Treasury of San Marco and the Marciana Library are displayed here.

CITY OF JUSTICE

“Whoever sees her with the sword and scales in her hand holding her faithful lion cannot say anything other than: that is the image of the Justice of Venice, or better, of Venice the Just, as in every respect is seen”.

Francesco Sansovino, 1562

As Venice grew in power and wealth, its leading families instituted a series of constitutional reforms resulting in a unique form of republican government, making a priority of political stability.

Venice was not a feudal landowning society with a dynastic ruler at the top. Rather, it was a republic, governed by a broad group of influential merchant families, who participated in its administration at all levels. The authority of the doge as head of state was tightly circumscribed and a complex system of checks and balances ensured that power was shared among all patrician families. Artisans and workers participated in the organization of society through guilds and confraternities. A deep, ongoing commitment to fairness and the rule of law made it possible for commerce to flourish as nowhere else.

Venetians embodied their ideals of enlightened government in the figure of Justice, bearing a balance and a sword, which was ubiquitous in official spaces and became identified with the personification of the city itself as Venetia, a beautiful woman wearing a crown.

III. CITY OF MARINERS

By the early 13th century, Venice had evolved from a lagoon economy to a maritime empire, having won control of the main strongholds between the Adriatic Sea and the Bosporus. Convoys of Venetian merchant galleys, protected by naval vessels, traveled all over the Mediterranean and north to London and Bruges.

Venetians were leaders in the development of accurate maps, necessary for navigation. On display in this room is one of the oldest examples of nautical cartography, the atlas produced in Venice in 1318 by Pietro Vesconte, containing charts of the Black Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic Ocean. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Venetian cartographers produced detailed maps of coastlines and ports, with webs of compass lines to assist navigators in charting their course.

The most famous Venetian traveler was Marco Polo, whose hugely popular memoir of his journey to China brought an immense body of new geographical knowledge to the West. Long distances were not unusual for Venetian merchants. Chinese porcelain from the Yuan and Ming dynasties in Venetian collections reflects an admiration for Asian art.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Venetian navy held the Ottoman Empire at bay in the Mediterranean. Indeed, Venice remained a mercantile and naval power into the 18th century.

THE ARSENALE AND THE ASSEMBLY LINE 1320

The expansion of the Arsenale in 1320 made it possible to build and maintain its entire naval and merchant fleet in a single facility, the largest industrial complex in Europe before the Industrial Revolution. All aspects of shipbuilding and munitions manufacture were centralized there. Venetians took a long view: the Arsenale had its own dedicated forests in the hills of the terraferma to supply timber for hulls, masts, and even charcoal.

Shipbuilding at the Arsenale is regarded as the earliest example of the factory assembly line. Hulls were stockpiled for future needs and could rapidly be turned into finished ships. The hull was towed from one workstation to another, to be fitted with masts, rigging, oars, weapons, and crew.

In 1574 the visiting King Henry III of France witnessed a galley completed, rigged, armed, and launched during the course of his mid-day meal – a spectacular demonstration of Venetian shipbuilding prowess.

IV. CITY OF MERCHANTS

“Now, what news on the Rialto?” asks a character in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, reflecting the renown of Venice’s commercial district and its entrepreneurs.

Venice began with no natural resources beyond fish and salt. Everything had to be imported. But its location was ideal as a center of trade between East and West – one of the few major cities on Italy’s eastern coast, but also close to the Alps and Northern Europe. Venice was already trading with Alexandria in Egypt in 828, when Venetian merchants brought back the relics of Saint Mark. Eventually Venetian trade routes extended all over the Mediterranean and north Atlantic.

Venice itself was an open bazaar, filled with imported luxury goods as well as items produced locally, such as tooled leather, jewelry, metalwork, majolica, paintings, silk, lace, fragrances, and above all, glass from Murano.

The merchants of Venice flourished thanks to the openness and fairness of the Republic’s political and judicial system and the support of the state for the infrastructure of trade. Venetians developed and leveraged sophisticated systems of coinage, banking, and insurance, providing building blocks of the modern economy.

THE DUCAT AND THE BOOK 1284, 1495

Of the many items produced in Venice, perhaps the most widely circulated and esteemed were the golden ducat (ducato) and the printed book.

The ducat, first minted in 1284, was a gold coin intended for large-scale trade and major payments. It soon became popular as a standard worldwide currency – “the dollar of the Middle Ages”. Produced under strict controls in Venice’s Zecca (Mint), the ducat’s design remained essentially unchanged for five centuries. Businessmen everywhere depended upon the consistency of its weight and gold content, guaranteed by the Republic. A 15th-century traveler to India found ducats in use there – evidence of the long reach of Venetian trade. The ducat remained a profitable export right up to the end of the Republic.

Shortly after the introduction of movable type in the 1450s, Venetians began to transform the technological innovation into a commercial enterprise. Soon there were hundreds of printers active in the city. Venetian merchants exploited their distribution networks to circulate a new product: books. By the mid- 16th century, Venice was the undisputed European capital of publishing.

The best-known Venetian printer is Aldo Manuzio (Aldus Manutius, 1449/1452-1515), who founded his Aldine Press in 1495. Its emblem of dolphin and anchor, based on a Roman coin, was recognized all over Europe. Aldo’s innovations in typography and book design – including italic type, the Roman font in use on our computers today, and the pocket book – made him the first true modern publisher.

V. REIMAGINING PIAZZA SAN MARCO

Doge Andrea Gritti (r. 1523-1538) understood the value of art and architecture as propaganda. He envisioned a Venice that would rival Imperial Rome, expressing its identity as the capital of an empire. One of Gritti’s main concerns was to provide a worthy setting for state processions.

Central to Gritti’s vision was the renovation of the Piazza and Piazzetta of San Marco, both of which had fallen into squalor. What followed has come to be referred to as Venice’s renovatio urbis – urban renewal – the most ambitious program of its type in 16th-century Europe.

The architect chosen to implement the program was the Florentine sculptor, Jacopo Sansovino. Doge Gritti encouraged him to move to Venice in 1527 after the Sack of Rome. Sansovino held the position of chief architect until his death in 1570. He cleared away the food stalls and shops that cluttered much of the Piazzetta. He went on to design and oversee the construction of new buildings in a classical style that evoked ancient Rome. The renovations continued after Sansovino’s death. By the end of the 16th century, the monumental center of Venice had become – and remains today – one of the grandest public spaces in the world.

STATEMENTS OF CONFIDENCE

The years around 1509 were terrifying for Venice. The Republic had become involved in the disastrous War of the League of Cambrai, with the major powers of Europe allied against it. Hostile armies overran the Venetian mainland in 1509.

The heart of the city was struck by a series of catastrophes, damaging the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, the warehouse of the German merchants, in 1504, the Campanile of San Marco in 1511, the buildings along the north side of Piazza San Marco in 1512, and worst of all, the entire Rialto business district in 1514.

The leaders of the Republic recognized the importance of rebuilding immediately, not only to maintain their economic infrastructure but as an assertion of their resilience and confidence in the future. Replacement or repair of each of these structures was promptly launched, with public funds. And subsequent decades saw even grander projects to embellish the city.

VI. REBUILDING THE PALAZZO DUCALE 1574, 1577

Venetians recognized the power of images. The Republic developed a rich iconography to express the superiority of its government and the benefits of its rule. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Palazzo Ducale, for centuries the seat of government – and today the site of this exhibition.

In 1574, a fire damaged the palace’s Sala del Collegio and Sala del Senato. Three years later, an even more devastating fire destroyed the Sala del Maggior Consiglio, home of the weekly meeting of the Great Council.

Devastated by this wound to their political system, Venetians made rebuilding a priority. While the project provided an opportunity to erect a grand new structure in a modern style, Venice’s leaders chose to recreate the Gothic façade, emphasizing continuity with the past. For the interiors of the rebuilt structure, they developed an elaborate program of allegorical and historical paintings demonstrating that the history of the Republic fulfilled a divine mission to defend freedom and faith. The best painters of the day, including Tintoretto and Veronese, were chosen to execute these plans.

PALLADIO: IN STONE AND ON PAPER

Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) is one of the most influential architects in history. His designs, based upon the principles of ancient Greek and Roman architecture, are reflected in buildings all over the world up to the present day.

Initially a stonemason, Palladio made a career designing villas and palaces around Vicenza, part of the mainland controlled by Venice. Encouraged by powerful patrons, in 1570 he published his studies in the lavishly illustrated Four Books of Architecture, a copy of which is on display here.

For Venice itself, he designed the church of San Giorgio Maggiore, across the basin of San Marco, providing a focal point for the new classical identity of the Piazzetta. In 1570, upon the death of Sansovino, he was appointed chief architect. He went on to design the church of the Redentore, a model of which stands in the next room. But some of his most ambitious plans for Venice remained unbuilt.

VII. PLAGUE 1576, 1630

As a port city, Venice was highly susceptible to plague. Outbreaks had appeared about once per generation since the 1340s. In response, Venetians developed a system that anticipated measures in use today. People showing symptoms were isolated and treated on a small island in the lagoon, the Lazzaretto. A second island, the Lazzaretto Nuovo, was added for arriving ships and people who had potentially been exposed. There they were required to remain for “40-odd” days – a “quarantina” (source of the word “quarantine”). To administer these rules, a public health board was created in 1485.

When plague appeared in Venice in 1576, the health board imposed a quarantine on people and goods entering the city. But leaders complained that the strictures were hobbling the economy, and the quarantine was suspended. This proved to be a disastrous mistake: soon deaths exceeded a hundred per day. The health board’s powers were restored. The state provided wood and food to those isolated at home and new clothes to the poor released from the Lazzaretto Nuovo. But these efforts came too late. The outbreak took more than 46,000 lives, a quarter of the city’s population.

Shockingly, the pattern was repeated in 1630: when the arrival of plague triggered restrictions from the health board, higher officials blocked them. The board’s physician was chastised for prejudice against commerce and liberty. The contagion spread, and again almost 47,000 died. The conflict between the competing goals of public health and business as usual remains all too relevant today.

VOTIVE CHURCHES AND PLAGUE SAINTS

Two of the great monuments of today’s Venice and two of the city’s most characteristic festivals owe their beginnings to the plagues of 1576 and 1630.

On 4 September 1576, Venetian senators overwhelmingly approved a vow that once the city was free from plague they would make a great procession, to be repeatedly annually, to conclude at a brand-new church dedicated to Christ the Redeemer, “in perpetual memory of the benefit received”.

It was decided to build the new church of the Redentore on the island of the Giudecca. The first procession to the site, over a temporary bridge, was held in 1577. Designed by Palladio, the church was consecrated in 1592.

During the plague of 1630, recalling the precedent of 1576, the doge made a vow to build another great church, this one dedicated to Saint Mary of Health. Construction on Santa Maria della Salute commenced the next year at an even more conspicuous site, employing designs by Baldassare Longhena. The annual processions to both churches continue today.

Venetians also prayed to their own protector from the plague, Saint Roch (San Rocco), whose remains had been brought to the city in 1485 by the confraternity dedicated to him – soon to be recognized as the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. Roch is frequently depicted in Venetian art along with another plague saint, Sebastian.

VIII. LINGERING GLORY

In the final 150 years of the Most Serene Republic, facing decline, Venetians retooled their economy once again to thrive as a center of artistic innovation and a mandatory stop on the European Grand Tour. The tradition of great painters continued with artists like Canaletto, Guardi, Longhi, and Tiepolo. New churches were erected in the Baroque style, most prominently Santa Maria della Salute.

The Teatro San Cassiano, inaugurated in 1637 as the earliest public theater in modern Europe, was joined by many more venues, where the new art form of opera flourished, to become one of Italy’s greatest cultural exports. Monteverdi, Vivaldi, Rossini, and Verdi all presented masterpieces in Venice. The dramatist Carlo Goldoni enriched the comic tradition with his observations of daily life in the city.

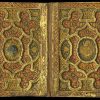

Venice itself became a splendid stage, its public life an almost non-stop festival, most famously during the long season of Carnevale. Everyone could be an actor, dressing the part with rich clothing and masks. The Republic continued to celebrate itself through rituals, accessories, and official robes that had barely changed in five centuries.

But the party ended in 1797, as Venice caved into the threat of French forces under General Napoleon Bonaparte, only 27 years old. The Venetian senate abdicated in favor of a revolutionary, pro-French transitional government. On 12 May 1797, Ludovico Manin, the last doge of Venice, formally abolished the Most Serene Republic of Venice, after some 1,100 years of existence.

FIRE AND RENEWAL AT SAN MARCUOLA 1789

Fires were an old enemy in dense urban centers, and Venetians had always responded with resilience. In the early 18th century, officials appointed a professor from the University of Padua to investigate modern firefighting techniques and recommend ways to tackle the problem. Among the innovations adopted were moveable hydraulic machines – early fire engines – based on English prototypes.

The fire that razed the San Marcuola district in November 1789 was one of the most devastating in the history of Venice. Beginning in an oil warehouse, it rapidly spread from house to house and lasted three days, terrifying witnesses, including artists who recorded the disaster. A painting of the scene displayed here shows the new hydraulic pump in action.

In the wake of the destruction at San Marcuola, authorities undertook an ambitious urban redevelopment program, producing a complete cartographic survey of the neighborhood and constructing new housing for those who had been displaced.

IX. AFTER THE SERENISSIMA

After the collapse of the Republic in 1797, Venice was passed back and forth between French and Austrian control for almost twenty years.

In 1807, Napoleon made his triumphal entry into Venice not from the sea, as was traditional, but from the mainland. A temporary triumphal arch was built in front of the church of Santa Lucia, a location that proved to be prophetic. Three decades later, this became the terminus of the railway line that connected Venice to the mainland. No longer an empire, no longer independent, Venice was no longer even an island.

As revolution swept Europe in 1848, Venetians cast out the Austrians and proclaimed the new Republic of San Marco, consisting of the city and many of its former territories on the terraferma. But independence was to last only seventeen months. The Austrians reconquered the mainland territories one by one, beating Venetian forces back to the city itself. Although the Republic’s assembly voted in April 1849 to resist “at any cost”, relentless bombardment of the city, coupled with famine and cholera, forced the Venetians to surrender in August. Another seventeen years of Austrian rule followed, during which Venetian hopes turned in a new direction.

JOINING ITALY 1846, 1866

“I was born a Venetian and I will die an Italian”. Ippolito Nievo, 1858

With the completion of the railroad bridge to the mainland in 1846, Venice joined the Italian peninsula. Politically, after the failure of the revolution of 1848-49, Venice’s hopes for an end to Austrian occupation became invested in the Risorgimento, the movement to unify Italy under King Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy.

The early operas of Giuseppe Verdi, especially their patriotic choruses, provided a soundtrack to the Risorgimento, giving expression to the long-frustrated desires of the Italian people. His Attila, which premiered at the Teatro la Fenice in 1846, depicted the birth of Venice by freedom-loving citizens fleeing Attila the Hun as the rebirth of the Roman Empire, rising anew from the ashes of its defeat like the legendary phoenix. One line inevitably evoked cheers: “You may have the universe, but leave Italy for me!”

The Kingdom of Italy was achieved in 1861, but Venice was not yet a part of it. Two paintings displayed here express the hopes of Venetians to join the new nation. Five years later, in 1866, after the defeat of Austrians and a referendum that overwhelmingly supported unification, Venice and the Veneto finally became part of Italy.

Once the capital of an empire, Venice was now a city among many in a new country, but a city that for the first time in seven decades was free to govern itself – a partner in the project of a united Italy.

“HOW IT WAS, WHERE IT WAS” 1836, 1902, 1996

On 14 July 1902, the Campanile of San Marco collapsed, weakened over centuries by lightning strikes, fire, and earthquakes, leaving a pile of rubble twenty meters high. That very evening, the council of the Commune of Venice met in emergency session and voted to rebuild.

Some questioned whether the new structure should exactly replicate the old one. “Why should the modern style not also be represented in the Piazza of Venice?”, one Viennese architect wrote. As the debate became heated, the mayor of Venice asserted the traditionalist position: “How it was and where it was – and so it shall be”.

The Modernists were routed. The rebuilt structure – apparently unchanged, although employing modern construction methods – was inaugurated on 25 April 1912, believed to be exactly 1000 years after original tower had been begun.

Like the Campanile, the Teatro la Fenice – prophetically named after the mythical Phoenix – embodies Venice’s ability to rise up after even the most disheartening disasters. First erected in 1792, the opera house was completely destroyed by fire in 1836 and again in 1996. Rebuilt both times, it stands today in its original location, “how it was, where it was.”

X. CAPITAL OF CONTEMPORARY ART

Beginning in the late 19th century, Venice’s leaders created new institutions to place it once again at the cutting edge of the visual arts, as it had been in the Renaissance. The Venice Biennale remains the oldest and most prestigious contemporary art exhibition in the world.

After World War II, American Peggy Guggenheim moved permanently to Venice, astounding the public with her collection at the XXIV Biennale (1948) and the opening of her house museum (1951), still Italy’s finest museum of 20th-century art. In addition to promoting foreigners like Jackson Pollock, Guggenheim nurtured a new generation of Venetian artists.

Host to the world’s oldest international film festival, held each year on the Lido, Venice was early to embrace the most influential art form of the modern age: the motion picture.

Venice’s setting and built environment have inspired many modern architects to develop proposals for the city – among them the Venetian Carlo Scarpa and foreign masters Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier. Though not always executed, these projects have presented important new architectural ideas to the world. Since 1980, the Architecture Biennale has been a major international showcase for design and urbanism. Venice has also been a pioneer in the re-use of historic buildings as spectacular locations for exhibitions and the display of contemporary art on an expansive scale.

Today the visual arts have become a backbone of a new economy for the city, encompassing a wide range of educational and cultural entities, public and private.

XI. ACQUA GRANDA

On 4 November 1966, the worst floods in recorded history hit Venice, with tides of 194 centimeters above mean sea level. UNESCO Director-General René Maheu launched an appeal to the world to help restore the countless damaged artworks and buildings.

Since then, 53 private committees have carried out nearly 2,000 restoration projects thanks to the funds raised in their countries. They have also financed – and continue to finance – studies, surveys, archival projects, research, training and teaching activities, publications, exhibitions, museum installations.

In 1987 an Association was created to manage relations with the Superintendencies and UNESCO. The Association, whose current Chairwoman is Paola Marini, has a permanent office in Venice, now headed by Carla Toffolo, to coordinate activities and support its members. Until 2016 the members cooperated in the framework of the UNESCO-International Private Committees Programme for the Safeguarding of Venice. In 2017 an agreement was signed with the Italian Ministry of Culture to provide technical-scientific support initiatives carried out in favor of public heritage or heritage assets accessible to the general public.

At present there are 26 committees from 12 countries. Over the years, their total commitment has been the equivalent of approximately 300 million euros today.

On 11 November 2019, Venice experienced the second worst flooding in history, at 187 centimeters above mean sea level. The Committees have mobilized once again in support of the city and its citizens, engaging with international scholars: Venice is an ideal of urbanism, built on a human scale and open to sustainable change.

THE FUTURE

As its history teaches us, Venice’s very existence after so many centuries is not a miracle, but rather the result of human ingenuity, effort, and long-term vision. Venetians have been able to thrive in this precarious setting because water and land and other opposing forces have been carefully kept in balance. Now challenges far greater than those in past centuries – both natural and man-made – threaten the city’s future.

Yet there are grounds for optimism. Innovative technology holds the highest tides at bay. Building on its status as a capital of art, Venice is reinventing itself as a center of knowledge, culture, research, and technology, with a growing economy of creativity.

Venice’s hopes depend on new generations of Venetians who can face the future with the same resilience and creativity as their predecessors, informed by the lessons of the past and by enduring principles that have guided Venice over the centuries: environmental protection, social equity, and the safeguarding of its most precious possession, its unique beauty and astonishing setting.

#NasciteRinascite #Venezia1600