Building and history

The Doge’s Palace

The Doge’s Palace in Venice is a masterpiece of Gothic art, a symbol of the city’s history, and the former residence of the Doge — the highest and oldest magistrate of the Venetian Republic.

With its unique structure combining Gothic, Renaissance, and Mannerist elements, the Doge’s Palace captivates visitors with its architecture and centuries-old history.

The structure is made up of three large blocks, incorporating previous constructions.

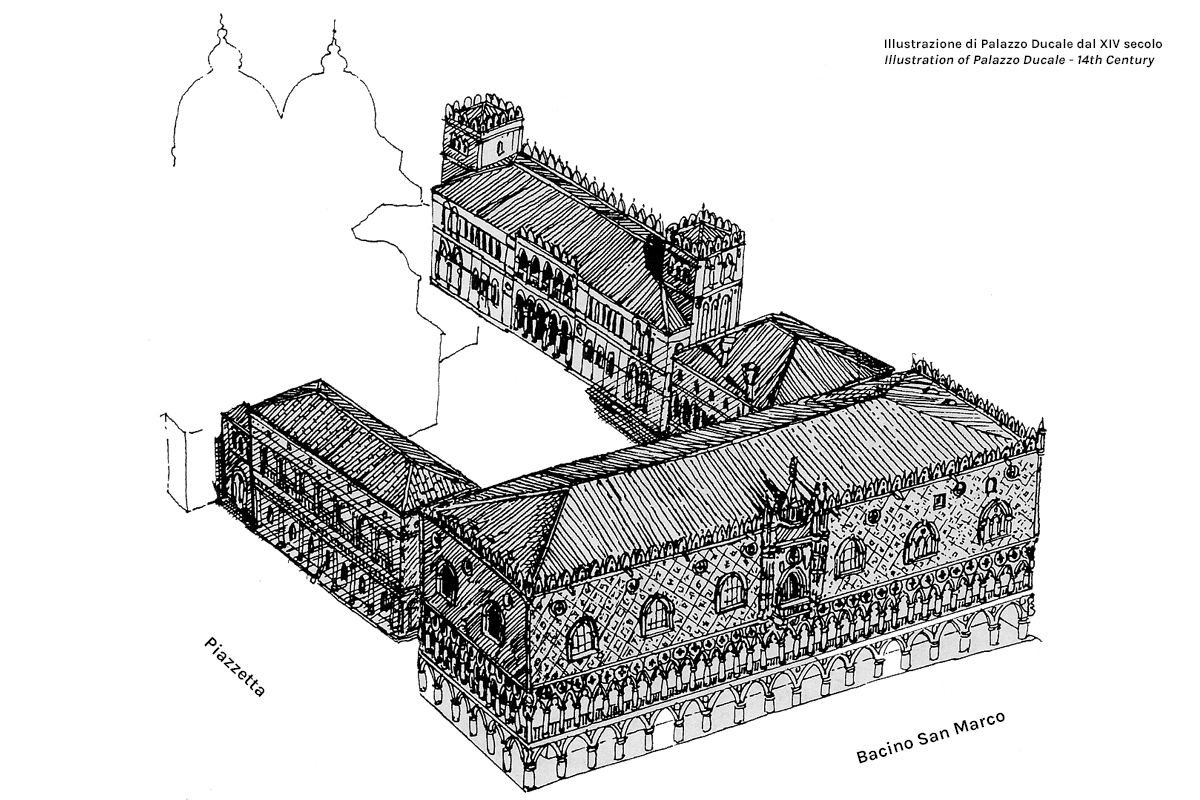

The wing towards the St. Mark’s Basin is the oldest, rebuilt from 1340 onwards. The wing towards St. Mark’s Square was built in its present form from 1424 onwards. The canal-side wing, housing the Doge’s apartments and many government offices, dates from the Renaissance and was built between 1483 and 1565.

The Porta del Frumento, located beneath the portico of the 14th-century façade, serves as the main entrance for visitors.

The origins

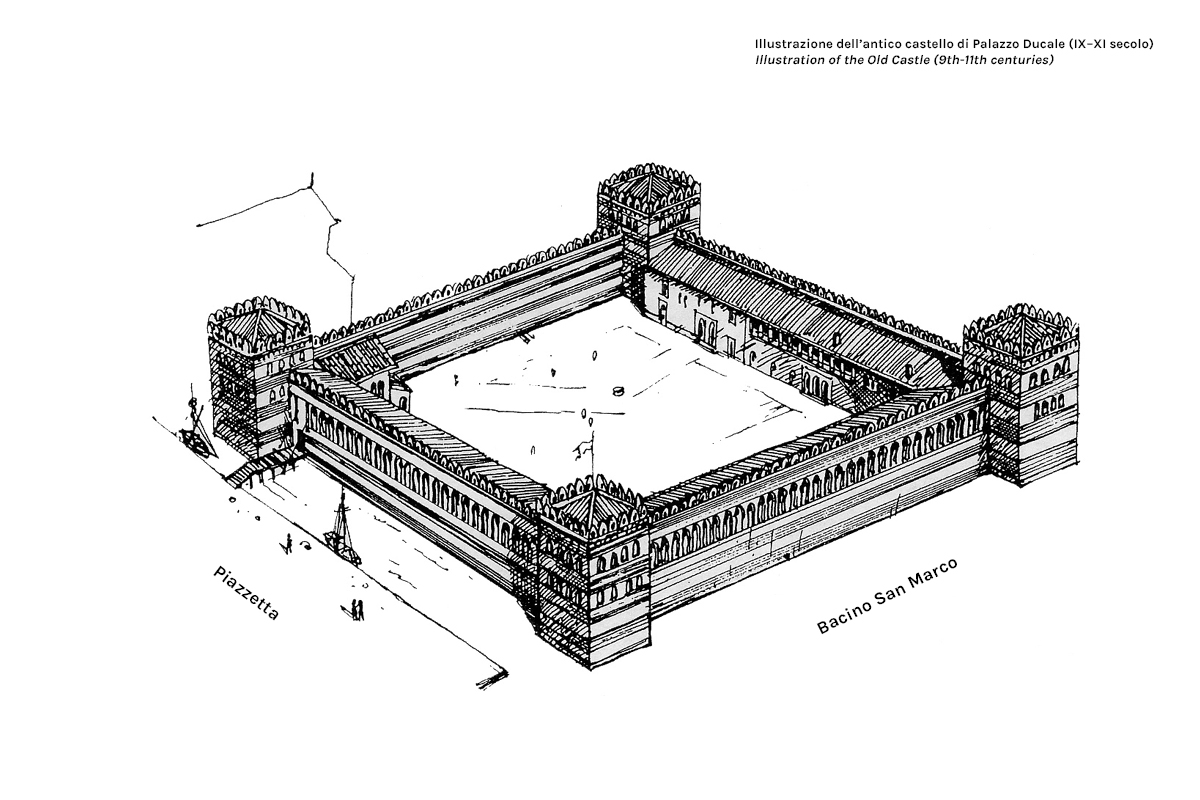

The origins of the Doge’s Palace date back to the 9th century, when Venice was beginning to establish itself as an autonomous center. Over the centuries, the building underwent numerous expansions and renovations.

In the 10th century, the Old Castle was built: the area now occupied by the palace likely consisted of an agglomeration of different buildings destined to serve various purposes, protected and enclosed by a substantial wall.

In the 12th century, Doge Ziani replaced the old structure with a new building open to the city, composed of two new wings: one facing the Piazzetta, intended to house courts and legal institutions, and the other overlooking St. Mark’s Basin, to house government institutions.

During the 14th century, the palace was renovated on the side facing the lagoon. The renewal continued into the 15th century, particularly on the wing facing the Piazzetta, under the direction of Doge Francesco Foscari.

After a fire in 1483, the palace was rebuilt and further expanded, introducing the new Renaissance architectural language to the building.

Subsequent fires in 1574 and 1577 damaged parts of the structure and its decorative elements, but the restorations preserved the original appearance of the architecture.

Up to the Present Day

In the 17th century, the New Prisons were built and connected to the palace by the famous Bridge of Sighs.

After the fall of the Republic of Venice in 1797, the Doge’s Palace housed important cultural institutions such as the Biblioteca Marciana (from 1811 to 1904). In the following years, a major restoration project preserved its historical appearance.

In 1923, the Italian State, owner of the building, appointed the City Council to manage it as a public museum. In 1996, the Doge’s Palace became part of the Civic Museums of Venice network.

A symbol and the very heart of the political and administrative life of the Venetian Republic’s thousand-year history, it is visited every year by millions of people who come to explore its history and admire its architecture and artistic treasures.

The Doge

The Doge was the oldest and highest political position in the Venetian Republic. The word comes from the Latin dux, which means leader and was the title given to the governors of provinces in the Byzantine Empire, of which the Venice lagoon was a part in the 7th and 8th centuries, when documentation of the first doges is to be found.

Over the centuries, the Doge gained power, with an elective position that, amid hereditary successions, conflicts, and violent deaths, became stable in the 8th century. Starting in the 11th century, as Venice had become independent of Byzantium, his powers were limited: he was supported by councillors and bound by the Promissione, a set of rules that regulated both his public and private life.

Elected by means of a very complicated voting procedure by the Great Council, the Doge was the only Venetian authority to hold office for life. Although he embodied the supreme representation of the Republic with countless and highly significant symbolic functions, he held no executive, legislative or decision-making power and was required to follow a strict ceremonial protocol.

At his death, solemn funeral rites were foreseen but the city was not in mourning, “because the Republic never dies”. His successor was nominated very rapidly with a solemn ceremony of investiture. The last doge was Ludovico Manin, who abdicated in 1797 when Napoleon Bonaparte’s soldiers entered Venice, thus marking the end of the ancient Republic.